The physical health of caged hens is frequently poor. Stress, disease, severe feather loss and brittle bones (weakened from lack of movement) are just some of the serious health issues hens may experience.

Due to selective breeding a hen will lay around 300 eggs per year, a huge increase from the 12 to 20 laid by her wild ancestor. Continuous egg production increases bone fragility and osteoporosis in hens kept in factory farms, as it takes a lot of to create eggshells.

Overcrowded conditions cause hens to experience high levels of distress and frustration, which can lead to aggressive behaviours like pecking and cannibalism. For hens kept in cages, feather pecking is a widespread problem.

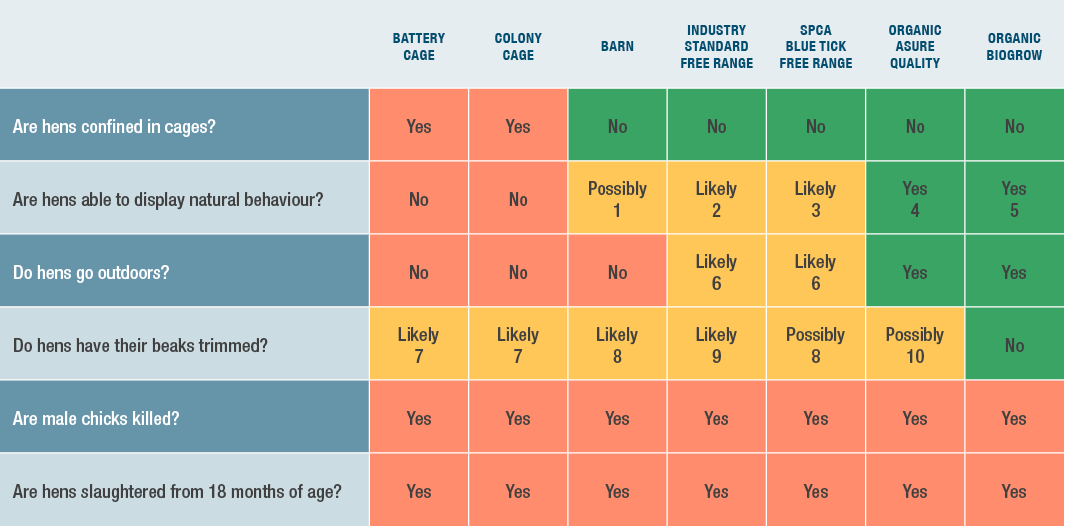

It’s common practice for egg farmers to remove the end of the hens’ beaks (“beak trimming”) to minimise damage from pecking. The chicks undergo this mutilation before they are ten days old. Depending on how much of the beak is removed, it can slice through sensitive tissues, causing pain.

When the number of eggs a hen lays drops below a profitable level she is of no more use to the farmer. She is removed from her cage and transported to the slaughterhouse. This usually occurs at around 18 months of age, at just a fraction of a hen’s natural lifespan of around 7 to 15 years.

Hens are pulled from the cages and carried upside down by their legs. It’s common for catchers to carry up to three hens at a time in each hand. The hens are then forcibly placed into crates for transportation to the slaughterhouse.

Rough handling when the hen is removed from the cage can be stressful and painful for the hen. A major concern during such handling is the likelihood of broken bones. Lack of movement due to space restriction is the leading cause of bone weakness and susceptibility to fractures.

The egg industry only requires female birds, so male chicks are considered an unwanted byproduct and are killed shortly after they hatch. Over three million day-old male chicks are killed annually in New Zealand. Male chicks are killed either by gassing with carbon dioxide or are minced up alive in a process called maceration. The industry also refers to this process as “‘instantaneous fragmentation.”

SAFE has helped lead the charge on freeing hens from a life in cages in Aotearoa.

And, worldwide, there has been a huge consumer movement away from cage eggs. SAFE part of the Open Wing Alliance. Initiated by the Humane League, the Open Wing Alliance is made up of 55 animal groups from around the world.

In response to this, many food retailers, restaurants, cafés, fast food outlets, hotels and food service and manufacture brands have pledged to go cage free. See the full list of international companies that are going cage free.

Consumer NZ reports that some egg brands give the impression they are “approved” or “certified” by the New Zealand Food Safety Authority (NZFSA). These claims are misleading. NZFSA does not approve or certify any egg brands. Its role is to register egg producers’ risk management programmes and audit their compliance with these programmes.

All producers with more than 100 birds are required to have a risk management programme. This is to ensure producers are meeting food-safety standards and has nothing to do with animal welfare.

In 2006, egg producers agreed to the voluntary labelling of eggs. While this has partly happened it is not industry wide or mandatory, nor is the labelling always accurate.

Words like “free to roam,” “cage-free” and images of the countryside and sunshine on egg cartons lead the average New Zealander to think of happy hens dust bathing and looking for food outside on green pastures. This is very different from the reality for hens — large sheds which confine tens of thousands of hens.

Shockingly, many “free range” hens may never experience being outside. To add further to the confusion, labels on eggs laid by hens kept in the new colony cages do not mention that these eggs are from caged hens.

The egg industry’s use of positive terms such as “farm fresh” and “colony laid,” misleads consumers and serves to divert attention away from the unpalatable reality of egg production.

In 2018, The Commerce Commission laid eight charges against a New Zealand egg farmer who sold millions of cage eggs as free range between 2015 and 2017. The Commission alleges that falsely labelled free range eggs were sold to retail and wholesale customers who believed that they were receiving free range eggs and were paying higher prices than for those from eggs laid by hens kept in cages.

In June of 2019, the New Zealand Egg Producers Federation responded to the scandal and announced its nationwide egg stamping program called “Trace My Egg.”

Aviary sheds are essentially enormous cages capable of housing up to 50,000 hens. Hens in aviary systems do not have access to the outdoors.

Like other systems, hens have fragile bones because of the continuous high egg production. Studies show hens housed in aviary sheds are more susceptible to breastbone (or keel) fractures from jumping off the multi-tiered levels to the floor or other perching levels.

Barn farming confines hens to large sheds with limited space and no access to the outdoors. The hens are provided with nest boxes and litter, but are still unable to express their natural behaviour or exercise properly. The maximum stocking density for barn egg farms is seven hens per square metre.

Like in other systems, hens are kept in dim lighting and are usually beak trimmed.

Many hens are unable to go outside at all. Some free range farms house up to 15,000 hens per shed – these unnaturally large flock sizes are stressful for the hens. When thousands of territorial hens are confined in one shed dominant hens often block exits. The maximum indoor stocking density for free range production is 10 hens per square metre.

Like in other systems, hens are kept on free range farms are beak trimmed.

There is no certification for “free range” in New Zealand. The code of welfare for hens kept to lay eggs does not specify basic standards, such as the size of their outdoor area and the maximum number of hens per flock. Most large industrial battery egg producers now also have free range operations.

Consumer NZ is currently calling for a mandatory consumer information standard for free range claims. The Fair Trading Act 1986 provides for these standards to be developed to specify information manufacturers must disclose to consumers. Consumer NZ have stated that the standard should require companies to list flock size on packaging.

Organic food production refers to food produced using only organic pesticides, herbicides, chemical fertilisers and antibiotics, not to the quality of life for the hen.

There are a number of different types of organic certification standards in New Zealand (such as AsureQuality Organic and BioGro). Organic standards require hens to be free range and flock sizes are restricted.

Like other egg farming methods, some organically raised hens are beak-trimmed, depending on the certification standards applied.

As a charity, SAFE is reliant on the support of caring people like you to carry out our valuable work. Every gift goes towards providing education, undertaking research and campaigning for the benefit of all animals. SAFE is a registered charity in New Zealand (CC 40428). Contributions of $5 or more are tax-deductible.